Key Takeaways

- 🏛️ Bankruptcy court approval: Judge Brian Walsh approved the $305 million sale of 23andMe to nonprofit TTAM Research Institute, founded by Anne Wojcicki, overriding objections from five states .

- 🧬 Genetic data protection: The deal prevents sensitive DNA data from going to pharmaceutical companies; TTAM pledges to maintain existing privacy policies and enhance safeguards .

- ⚖️ Legal objections: California AG Rob Bonta contends the sale violates state law requiring explicit consent for genetic data transfers, hinting at potential appeals before July 7 .

- 🔄 Founder’s return: Wojcicki regains control after resigning during bankruptcy proceedings, positioning TTAM to continue 23andMe’s mission as a nonprofit entity .

- 🛡️ Customer safeguards: TTAM commits to advance deletion notices, two years of identity theft monitoring, and a Consumer Privacy Advisory Board .

The Bankruptcy Court’s Decision Explained

A U.S. Bankruptcy Judge, Brian Walsh in St. Louis, formally approved the sale of 23andMe’s assets to the TTAM Research Institute on June 30, 2025. This decision came after months of legal battles and objections from multiple states concerned about genetic privacy. The judge modified standard procedures to allow the deal to finalize after July 7, much earlier than the typical 14-day waiting period, citing the urgency of resolving the company’s financial collapse .

Walsh acknowledged genetic data sales are “a scary proposition” but noted lawmakers haven’t prohibited them. He argued blocking the sale could mean “missed opportunities” for research, though he didn’t specify what those might be. Importantly, he viewed TTAM not as a new owner but as a continuation of 23andMe under familiar leadership .

Why States Fought the DNA Data Transfer

Genetic data isn’t like selling office chairs or real estate, it’s deeply personal and unchangeable. Initially, 27 states sued to stop 23andMe’s sale to pharma giant Regeneron, fearing misuse of health and ancestry information. Though most states withdrew objections after TTAM’s higher bid and privacy pledges, five, California, Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah, dug in .

California AG Rob Bonta spearheaded the opposition, arguing the transfer blatantly violates the state’s Genetic Information Privacy Act (GIPA). This law mandates explicit opt-in consent before genetic data is sold to third parties. Bonta’s team insists TTAM qualifies as a “third party,” regardless of Wojcicki’s ties to 23andMe. They’re now “evaluating next steps,” which could include an appeal before the July 7 deadline .

How TTAM’s Bid Beat Regeneron

The path to TTAM’s victory was messy. In May, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals won an auction to buy 23andMe for $256 million. Backlash was immediate: customers deleted data, states sued, and privacy advocates warned of dystopian outcomes .

Then entered Anne Wojcicki’s nonprofit TTAM Research Institute, established in May 2025 explicitly to acquire 23andMe. Their $305 million bid, coupled with binding privacy commitments, convinced 23andMe’s board to reverse course. Regeneron declined to counterbid, quietly exiting the fight . TTAM’s offer wasn’t just higher, it promised to honor deletion rights, restrict future data transfers, and add monitoring services. For the board, this balanced profit with public trust .

Anne Wojcicki’s Return to Leadership

Anne Wojcicki’s journey here’s been rocky. She co-founded 23andMe in 2006, but resigned in March 2025 when the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Earlier, she’d tried taking it private, but the board rejected her plans amid cash shortages and sinking valuations (from $6 billion to ~$100 million). Her exit followed mass director resignations and layoffs cutting 40% of staff .

With TTAM, she effectively circles back. As founder and CEO of the nonprofit, she reclaims control of the company’s assets and its 15-million-user DNA database. In statements, she frames this as a mission reset: advancing “DNA, the code of life, for the public good” without shareholder pressures . Critics question if her past leadership troubles will resurface, but supporters see it as a chance to fix what failed.

Privacy Promises TTAM Must Keep

To ease fears, TTAM made legally binding commitments around data use:

- No policy changes: Adhering to 23andMe’s existing privacy terms indefinitely .

- Deletion rights: Customers can still erase data or opt out of research anytime .

- Breach protections: Two years of free identity theft monitoring for users .

- Restricted transfers: Barring future sales of genetic data if TTAM faces bankruptcy .

They’ll also email all users about the sale, explaining deletion options. Plus, a new Consumer Privacy Advisory Board will oversee compliance. Still, skeptics like Kyle, an Ashkenazi Jewish customer who deleted his data post-2023 breach, doubt any system is foolproof. “If that information gets into the wrong hands it’s very dangerous,” he told NPR .

Why Genetic Data in Bankruptcy Is Legally Murky

This case highlights gaping holes in U.S. genetic privacy law. While GINA bars health insurers from using DNA against you, no federal statute governs how bankruptcy courts handle genetic assets. Laura Coordes, a bankruptcy expert at Arizona State University, notes this forced states to “react” instead of relying on clear rules .

Judge Walsh himself urged legislative fixes, writing that the upheaval “will spur meaningful thought about data privacy protections.” Until then, companies holding sensitive data risk similar chaos if they fail. 23andMe’s settlement funds from this sale may compensate breach victims, but it’s a band-aid fix .

What Happens Next for Customers

For 15 million 23andMe users, key dates loom:

- Pre-closing notice: Emails from TTAM explaining the sale and how to delete data will arrive soon .

- July 7 deadline: Opposing states must appeal by 11:59 PM CT to halt the sale .

- Post-closing options: Accounts remain active unless users opt out; research participants can withdraw consent .

If you’re uneasy, experts suggest:

- Review notices: TTAM’s email will include deletion steps.

- Download data: Retrieve ancestry/health reports before deleting.

- Monitor accounts: Check for unusual activity post-sale.

Broader Lessons for Biotech Companies

23andMe’s collapse wasn’t just about privacy, it was a business model failure. Customers used kits once, then disengaged. The company couldn’t monetize repeat services or drug research fast enough to offset costs. After a 2023 hack exposed millions of profiles, trust eroded further .

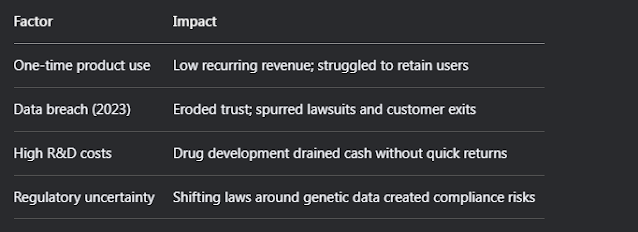

Table: Why 23andMe Failed

For rivals like AncestryDNA or MyHeritage, the takeaway’s clear: diversify revenue, enforce ironclad security, and lobby for clearer laws. Biotech firms holding DNA must plan for worst-case scenarios, before bankruptcy looms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I delete my 23andMe data before the sale?

Yes. TTAM will email all users before closing the deal (expected mid-July 2025), explaining how to delete accounts or biological samples. You can also initiate deletion now via 23andMe’s website .

Will my data be used differently under TTAM?

Unlikely. TTAM vows to maintain existing privacy policies. Since 80% of users already consented to research, their data will fuel nonprofit studies. You can opt out anytime .

Why is California still objecting?

California believes the transfer violates its strict genetic privacy law, requiring explicit consent for data sales. AG Bonta argues customers didn’t consent to TTAM as a new owner, regardless of its nonprofit status .

How does TTAM being nonprofit help?

Nonprofits prioritize public benefit over profits. TTAM can’t sell data to advertisers or insurers. Profits from services like ancestry kits must fund research, not shareholders .

Could the sale still be blocked?

Only if objecting states appeal by July 7 and a court grants a stay. Given the judge’s firm stance, legal experts consider this unlikely .

Comments

Post a Comment